Drunk birds

At some point in the early 2010s, variations of a pop-science news story about bird sexuality began to circulate online. study says pollution makes birds gay and gay by mercury, read the headlines. The story was about the fact that pollutants leaking into the environment are changing the hormone systems of animals and leading to new traits and behaviors. In the case that has gotten the most attention, high levels of mercury in wetland habitats are altering the ‘pairing behavior and reproductive success’ of a species of white ibis. Scientists observe that, rather than heterosexual coupling and reproduction, some white ibises now prefer same-sex relationships. One image accompanying a news item shows a pair of male ibises strolling together along a shoreline, looking very gay indeed.

The tone of these stories is one of alarm. And it is surely alarming that human-made pollutants are altering the endocrine systems of other species. White ibises who do not breed with each other are more likely to go extinct, further reducing the planet’s rapidly diminishing biodiversity. The gay birds represent yet another example – part of a long list – of human behavior altering the planetary ecosystem in unexpected and damaging ways.

Yet the news stories’ common focus on the birds’ sexually ‘atypical’ behavior indicates another type of alarmism, too. Queerness, here, is presented as the result of a toxic environment, an unnatural aberration from the birds’ ‘natural’ straight and reproductively focused orientations. Aligned with the toxic and the unnatural, the birds are anthropomorphized and their sexualities moralized according to human biases. In an essay about the ibises, health scientist Anne Pollock points out that ‘posing intersex characteristics as the sine qua non of harm to our environment is a move steeped in heteronormativity.’ According to Pollock, commentators may couch their concern in terms of extinction, but nonreproductive erotic relationships are the underlying fear.

Pollock argues further that, if we are to anthropomorphize animals to the extent that we can even call them gay, we must also consider the anthropomorphic possibility that their new sexual identities (assuming, probably wrongly, that their gayness is entirely novel, rather than previously unobserved) are not unpleasant for them. Perhaps the gay birds are enjoying their new carefree, childless lifestyle. Perhaps some of these birds, like some humans, find some aspects of reproduction a burden. ‘For biologists, reproductive success is often understood to be the final cause of animal existence,’ writes Pollock. ‘Yet from whose perspective is reproductive success the ultimate definition of “success”? God’s, Darwin’s, ecologists’, or the animals’?’ We can’t know what fulfilment is to the animals, but we have to assume it isn’t the same as ours. More to the point, human desires differ among the species – can’t theirs?

While sympathizing with preservationist concerns and lamenting the possibility of ibis extinction, Pollock inquires why some behaviors, and some environments, are deemed natural or unnatural; why human-led climate change gets so much attention only in some circumstances; why bird sexuality is any of our business. It’s true that the birds have not had a choice in the matter when it comes to their environmental pollution or hormonal regulation – but then again, who does? Humans too absorb a number of extremely toxic pollutants without prior consent.

In this toxic world, GMO crops are vilified as suspiciously artificial, unhealthy and unnatural; simultaneously they are championed for quick reproduction with the capacity to feed large populations. Seedless grapes – fleshy globes bred devoid of seed-embryos – are weird but convenient and delicious; yeast is good for the gut unless it overbreeds, in which case you need pills and ointment. Opium is illegal but opiates are sanctioned and gluttonously overprescribed for profit. With our incredibly porous bodies and our mutated ecologies, we can hardly pretend there is a state of unmodified, unpolluted, sober nature in which animals like us could – or should – exist and bear fruit.

There are also intoxicating effects to what we consider toxic. ‘Yeah, maybe these birds are “fucked up” by their polluted environment,’ Pollock writes, but ‘it can be fun to be fucked up’. What is recreation and what is poison is entirely a question of cultural attitude. A state of intoxication might be dangerous, but it might also be pleasurable, and there is nothing particularly aberrant about it: when it comes to sobriety as a default ‘natural’ state, the last centuries have been a historical exception in the West. Throughout the Middle Ages, for example, people drank beer or wine because water wasn’t potable. Even if drunkenness doesn’t fit into our current understanding of purity, many other chemically altered states do. Pharmacological substances are sanctioned when they contribute to what is considered mainstream productivity, wellness or normalcy. Conversely, pharma-power has been reclaimed in opposition to conservative purity politics and endlessly shifting ‘natural’ baselines – consider the gleeful endocrinological intoxication and chemical dependence implied by Paul Preciado’s well-known title Testo Junkie. (Or the Xenofeminist Manifesto’s closing line: ‘If nature is unjust, change nature!’ – as in, nature doesn’t exist, so let’s fuck with it according to our own desires.)

Despite their endocrinological metamorphoses, and despite their declining reproductive rates, the gay ibises seem to be living long and healthy lives – and enjoying intimate relationships with each other. Pollock likens their state to what some theorists might call ‘queer sociality’, where any moral, and in this case anthropomorphic, distinctions between toxic and safe, pure and artificial, chemically neutral and chemically enhanced, may be reclaimed and/or rendered irrelevant through the sheer intoxicating nature of togetherness. The birds are still having an erotic and social life, if not a reproductive one, and that is still a life. Especially in an age of mass extinction, should not every form of life be celebrated, congratulated?

In a landmark book of queer theory No Future, Lee Edelman claims that politics as we know it operates on the ‘presupposition that the body politic must survive’ and that queerness provides an alternative political framework. As a term and a lived experience, queerness ‘names the side of those not “fighting for the children”, the side outside the consensus by which all politics confirms the absolute value of reproductive futurism’ – and this is where ‘queerness attains its ethical value’. Like Edelman and many others, Pollock provokes us to rethink ‘the capacity for intergenerational life’ as the telos of all life, but takes this further to suggest this question applies even when it comes to other species. This is of course a provocation for humans to think anew about our own teleological drive toward intergenerational life in relation to all other life, especially when human activity is exactly what has fucked up the birds so much.

Paradise rot

Jenny Hval’s short novel Paradise Rot presents love as an ambivalent experience, both toxic and intoxicating. A young Norwegian exchange student, Johanna, moves to a beach town in Australia. Struggling to find housing, Johanna eventually moves in with Carral, a waify Australian woman living in a strange house in a former brewery. The brewery is disused but doesn’t seem to have stopped fermenting. Everything in the building is rotting. Mushrooms sprout from the bathtub grout; disintegrating apples overflow from the trash can. Insects circle. The decomposition is lively and sensorially overwhelming. The cheap walls, built to divide the formerly cavernous space, are paper thin, and Johanna can hear everything in the house – from water dripping to Carral peeing or even breathing. And Carral herself, increasingly fragile, sickly, somnambulistic and clingy, seems to be decomposing into the stew.

Soon after Johanna moves into the brewery, Carral starts sneaking into her bed at night. It’s not clear whether Carral wants sex; she mainly seems to want someone to cling to, to rub up against, to cry with, and to assure herself that she exists by dint of contact. It’s not clear either whether Carral is entirely awake for these dreamlike encounters, which become increasingly erotic. The lovers soak into each other and the furniture, the floorboards. Carral wets the bed, pee soaking Johanna’s clothes. Johanna gets her period and the blood soaks the sheets.

In a state of what resembles chemical dependency, Johanna finds it harder and harder to leave the house or to be away from Carral, who is constantly persuading her to stay home, who needs Johanna to feed her, take care of her, hold her, touch her. Carral spends most of her time listlessly flipping through an erotic novel or passed out on the dank sofa. Johanna watches her, obsesses over her, loves her, despises her. Their desire does not flow but oozes between them, threatening to submerge Johanna. She struggles against the urge to become part of the damp house with its fungal occupants and its compost heap.

Johanna’s descriptions of their bodies indicate a troubling mingling. As when she considers the effect of Carral’s touch on her skin: ‘Sometimes I was sure I could feel little sprouts appear under the skin where she’d breathed’; or the sensation of Carral slipping into bed beside her: ‘I felt the same soft skin melt against mine as I’d felt earlier, touching the mushroom cap. I didn’t move but let her envelop me.’ Ostensibly Carral can’t get Johanna pregnant, but Johanna is continually preoccupied with what will happen to her once Carral has penetrated her, gotten under her skin, to the extent that she feels like ‘anything can inseminate me now . . . anything can get into me.’ Her desire to be taken over is matched by her fear of being taken over – from the inside out, impregnated or infected by something that decomposes her. And she explains the threat in terms of impregnation, as if she has no other language at hand to explain her fear. Rather than suggesting that somehow impregnation is at the root of all sexual desire, the implication is that nonreproductive (and even nonhuman) penetration can be just as fulfilling/frightening, life-sustaining/life-destroying, as any other kind.

Incursion

Because it can be both toxic and intoxicating, erotic love is ambivalent. One desires to be taken over: absorbed, enveloped, dissolved, decomposed. And one desires just as strongly to retain one’s individual shape. In this way, Anne Carson describes the ambivalence of the erotic encounter in her book Eros the Bittersweet. The ‘incursion’ of Eros disintegrates the self, disturbing its homeostasis. The self finds this both painful and pleasurable. It is only due to an incursion, after all, that the self can recognize itself as such. In the process of that internal stirring up, the self realizes where its boundaries have been, and then desires to retain them. The lover has to ask, ‘“Once I have been mixed up in this way, who am I?” Desire changes the lover.’ Carson describes this change as both bitter and sweet. She adapts the term from a fragment of poetry by Sappho:

Eros once again limb-loosener whirls me

sweetbitter, impossible to fight off, creature stealing up…

Where others have translated Sappho’s term glukuprikon as the colloquial ‘bittersweet’, Carson translates the word – itself a neologism Sappho likely invented – as ‘sweetbitter’. For Sappho, Carson argues, first the sweetness of love intoxicates, and then its bitterness signals its potential toxicity. First delicious, then repellent. Then both. Because of this vacillation, Carson calls the word sweetbitter, glukuprikon, as a sticky one: two opposing words for opposing sensations stuck together. Being in love is a sticky place. One wants to stay and one wants to escape. One wants to open and one wants to close.

According to Carson, the boundary-disintegrating experience of erotic love is akin to the experience of encountering the written word. Reading requires something particular of the reader’s mind and does something particular to it. In an oral culture, where sound is the primary mode of communication, information enters and exits consciousness in a fluid way, requiring less focused concentration than looking, and much less concentration than reading. But reading requires one to block out the other senses to concentrate. A communication system based on literacy demands visual focus in an exercise of self-control. And when written, information becomes a fixed entity rather than flexible, open-ended, alive, updatable. In an oral culture, whatever gets committed to memory and repeated might be incorporated into a story. But a written story is alienated from the storyteller, converted into the corpus of text as opposed to the body of the person who speaks.

Literacy changes the way people relate to one another. Writes Carson, ‘Oral cultures and literate cultures do not think, perceive or fall in love in the same way.’ Letters compose words, which in turn compose letters that lovers can send to one another. Carson recounts numerous ancient stories of lovers separated by distance but bridged by the written word. ‘It is letters that pose the dilemma of absent presence for lover and beloved,’ writes Carson. Like the space between letters, the space between lovers is necessary to make meaning from their union. Without the gap, there is no longing to be felt and no meaning to be made. Texts require boundaries. Selves require boundaries. Only when a boundary materializes can it become a site for transgression.

In a society of the written word, Eros is figured as a threat. If selves have membranes separating, individuating and protecting an individual from the outside, the dissolution of the self that is occasioned by, demanded by, love becomes frightening. Love stories in the Western tradition tend to be written along a common arc: the lover is seized or dismantled by the object of desire, becoming incapacitated, crazy, or desperate. Cupid’s arrow jabs the skin and renders one helpless, that is to say, no longer in control of oneself, one’s desires or one’s boundaries. Under thrall of an outside force; invaded, body-snatched. Love entails both the risk and the pleasure this sticky decomposition occasions.

‘Your story begins the moment Eros enters you,’ summarizes Carson. ‘That incursion is the biggest risk of your life. How you handle it is an index of the quality, wisdom and decorum of the things inside you. As you handle it you come in contact with what is inside you, in a sudden and startling way.’ The writer, like the lover, reaches toward a future fiction when two become one – lover and beloved, or writer and reader – trying to bridge an impossible gap, to overcome the boundary that itself creates the possibility for the pleasure of its transgression. Yet if the boundary were to be truly dissolved, the site of desire would be erased. The Western story of desire, says Carson, is premised on self-enclosure.

Rachel Rose, still from Enclosure, 2019. Courtesy of the artist, Pilar Corrias Gallery, London and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome.

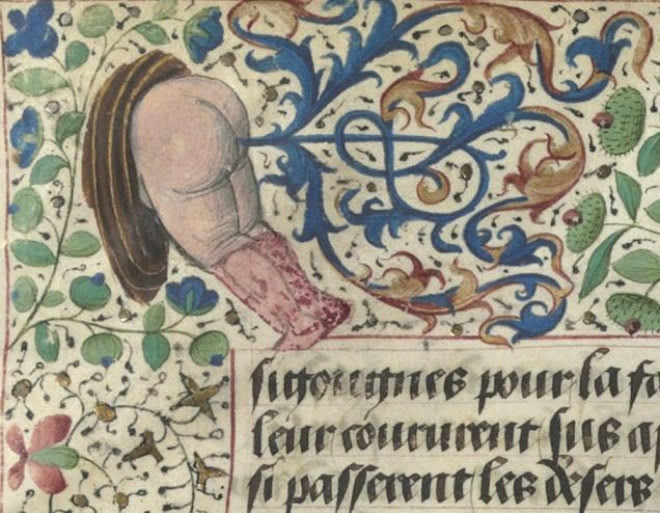

The history of self-enclosure could also be told in political and economic terms. As theorists such as Barbara Ehrenreich, Deirdre English and Silvia Federici have explained, the delimitation and privatization of (especially the female) body occurred simultaneously with the expropriation, delimitation and privatization of common land and resources throughout the High and Late Middle Ages. An extractive capitalist system requires that, like the natural world, bodies become resources, which requires creating boundaries between individuals. Individuals can then be combined into discrete family units, further enclosed micro-economies whose productive labor is extracted and whose reproductive labor is invisibilized. In the words of Erica Lagalisse, ‘just as land, air, and water must first be enclosed as “resources” before the capitalist may profit from the commodities they are then used to produce, so were women enclosed as (reduced to) mere bodies . . . insofar as it served to enforce the logic of private property, wage work, and the transformation of women into (re)producers of labor.’

Taken together, Carson’s historical understanding of self-enclosure as the premise for erotic love, and the story of self-enclosure as the premise for capitalism, suggests that to transgress one of these boundaries may be to transgress the other. It suggests, in Alain Badiou’s words, a ‘kind of secret resonance’ between the intensely erotic and the intensely political – between the body and the body politic. If, as Edelman writes, politics itself is built on the notion of a self-perpetuating body politic that must survive by reproducing itself – by mating – then nonreproductive ‘queer oppositionality’ fundamentally challenges the ‘structural determinants’ of politics as such. Assuming the ‘structural determinants’ of the self-perpetuating body politic include those of sex and gender among humans, they must also include notions like human/non-human, animal/plant, living/nonliving. A queer oppositionality must transcend structural determinants within the category of humanity. But to do so, it may need to disrupt the essentialisms and enclosures pertaining to the category of species being itself.

Reproduction is a feminized practice; but trying to degender or distribute that work among all humans only essentializes – encloses – it further. Uncoupling the erotic from the reproductive is not enough either; another set of enclosures within and around humanity simply arise. The queer oppositionality to come will not simply be de-gendered but it will be de-species. It will be ecologically distributed.

Bad graft

Karen Russel’s 2014 short story ‘The Bad Graft’ is about an unwanted, unexpected, erotic interspecies incursion. The story opens as a young man and a young woman embark on a runaway road trip through the American Southwest. They’ve eloped with nothing but a car and some cash, driving toward the great unknown. So wrapped up in each other and their love, they find the danger of the futurelessness exciting enough to overcome the impracticality of it all.

Exhaustion and disorientation begin to set in as the gas and the money run low. They stop when they finally reach the only destination they’ve agreed upon, the Joshua Tree national park in California. A park ranger stops their car to notify them that they’ve fortuitously arrived at a golden ecological moment: ‘their visit has coincided with a tremendous blossoming, one that is occurring all over the Southwest. Highly erotic, the ranger says, with his creepy bachelor smile. A record number of greenish-white flowers have erupted out of the Joshuas. Pineapple-huge, they crown every branch.’

So fertile is this hot desert, usually so dry and barren, it seems as if it’s bloomed just for their arrival. The ‘orgy’ of the Joshua trees’ pollen – and the pollinating moths with whom they have a symbiotic relationship – is so great that it overwhelms the couple as they approach the ‘hilariously alien’ trees. Overcome by the sight, suddenly the girl (the narrator calls her a ‘girl’) feels a stabbing pain in her finger. One of the trees’ trillions of tiny spines has pierced her hand. The narration zooms in as the pollen from the plant enters her body through the wound and mingles with her blood. The narrator calls this moment ‘the Leap’: the instant at which one species crosses over, attempting to mate with another.

The pollination, in this case, is a nonconsensual accident. The girl soon feels a heat pulsing in her abdomen, like cramps, which then crawls up her spine. The intoxicating pollen storm becomes a toxic one when it punctures her skin. The desire of the plant to pollinate and grow in the soil is not a desire compatible with her body, nor with the plant’s own desires.

Following this mismatched alien incursion, the girl’s body becomes a kind of resentful host for the equally resentful plant. The plant’s perspective is given a voice at times: ‘At first, the Joshua tree is elated to discover that it’s alive: I survived my Leap. I was not annihilated. Whatever “I” was.’ But the joy at having survived is quickly overtaken by frustration. The girl is likewise overcome by an immunological response to her accidental implantation. Why was she the one who ended up as host, and not her boyfriend?

The plant’s desires begin to impress themselves onto the girl. What does the plant desire? To sink roots. To stay in the desert and survive a thousand years without moving. The girl is overcome with irresistible urges to be outside, to be flat on the ground, to be alone. Her boyfriend, however, ‘has no clue that he is now party to a love triangle.’ All that he ‘perceives is that his girlfriend is acting very strangely’. The plant has penetrated her more completely than her boyfriend ever could.

Meanwhile, the plant learns to enjoy or at least to tolerate some of the sensations it gains through the girls’ sensory apparatus: the sight of colors, the ability to move its limbs. Sometimes it feels intoxicated by the possibilities. In turn, sometimes she feels intoxicated by its presence. Plant and girl reach an uneasy symbiosis as her hormonal cycles and its annual cycles overlap in different ways, sometimes allowing them to coexist and sometimes forcing them to battle for dominance within her body. Her relationship with her boyfriend disintegrates, as much from the strangeness of her behavior as from the fact that she is not so passionate about him anymore, now that she is passionate about other things. She will be forever in thrall to her own competing desires: stay whole; be taken over completely. The plant inside her feels somewhat the same.

The gift

The poet Lewis Hyde asks: ‘If we open ourselves to love, will love come in return, or poison? Will new identity appear, or the dead-end death that leaves a restless soul?’ Hyde, like Carson, looks to poetry for descriptions of love’s incursion and the risks it carries. If love decomposes the self’s boundaries, will it revivify the self as well? What forms of penetration, if any, does love require? As a case study of a life entirely open (perhaps too open) to the incursions of love, Hyde turns to Walt Whitman, weaving fragments of Whitman’s poetry into a biographical account of Whitman’s many loves.

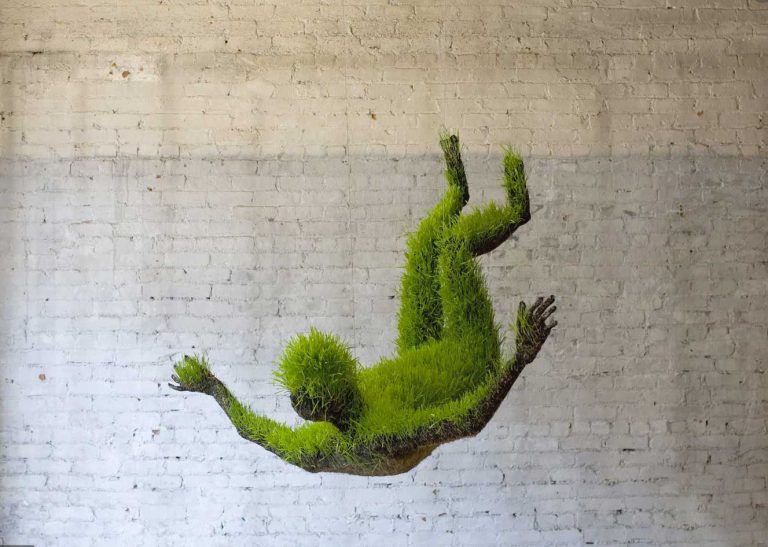

Whitman was romantically frustrated for most of his life. He had a number of relationships with other men that, despite his longing, never amounted to the subsumption of self-in-other that his poems suggest he so fervently desired. He found solace, joy and reciprocity in other places, notably a hospital for wounded Civil War veterans, where he spent months at a time tending to the patients. But mainly, throughout his life, he found rapturous self-dissolution in nature, the love of which overtook him, and the love of which forms the basis for the writing he is best known for. In many poems, he expresses a continual desire to be penetrated by the natural world, to be overgrown by plants, to become compost for the regeneration of life, human and nonhuman alike.

In one poem, first called ‘Poem of Wonder at the Resurrection of Wheat’ and later retitled ‘This Compost’, Whitman marvels at processes of decay and purification. The ground, which received so many of the soldiers he watched die, wounded and sick and corrupted as their bodies were, has converted them into raw material for fresh life, grass that cradles the living who walk upon it. Whitman exults:

What chemistry!

That the winds are really not infectious!

[…]

That when I recline on the grass I do not catch any disease!

Though probably every spear of grass rises out of what was once a catching disease.

Whitman’s encounters with soil and grass are eternally sexy. His desire for the earth is erotically charged precisely because it is a struggle with boundaries and separations – because the earth erodes these boundaries and separations through rot and regeneration. As for many mystics, the nonhuman world provides for Whitman a philosophical and aesthetic mode or encounter, which serves as a model for understanding and transcending anthropocentric erotics. ‘Whitman does not deny his hesitancy and fear, but in the end he opens the skin, accepting what is a poison to particular identity so as to receive a higher sweetness for the durable self.’

‘This Compost’ is borne of Whitman’s risk-fearing and hesitancy when it comes to human relationships. But ‘in the poem at least, Whitman resolves his hesitancy by fixing his eye on the give-and-take of vegetable life in which the earth “grows such sweet things out of such corruptions.” In apparent decay the man of faith recognizes the compost of new life.’ Some have read Whitman’s exultation of nature as a last-resort necessity of a man who did not find the fulfillment of Eros in life. But Hyde interprets Whitman’s nature-worship as an erotics beyond what can be accounted for by any single human relationship. Whitman’s work and life embody an erotic give-and-take, risk-and-reward, that disregards species being. Perhaps Whitman was so desirous of incursion that his desire could not be contained by the reductive set of human options.

Hyde’s extensive writing on Whitman forms a section of his book The Gift, the thesis of which is that the creative act – artistic creation – is fundamentally an act of generosity which may be accounted for by commodity systems such as the market economy, but which forever evades total capture by those systems. Hyde makes a sojourn into anthropological surveys of cultures with gift-giving economies, and considers the way gifts have today been converted into philanthropy and commodified to enter the exchange economy. But unlike commodities, a gift’s value only increases as it circulates, claims Hyde. The gift contains within it ‘the mystery of things that increase as they perish’ – like compost. For this reason, the circulation of the gift is an undeniably erotic exchange.

In Whitman, Hyde seeks evidence of a life that was all gift, understanding Whitman as a person whose generosity and erotic desire became ecologically distributed. Hyde looks to poetry itself as evidence for the way creative expression is regenerative: the poem does not belong to anyone. Poems, like bodies, are ‘independent of intentions and authors . . . Their boundaries materialize in social interaction’, writes Donna Haraway. For this reason the poem is a nonreproductive yet a highly erotic gift. One might use a poem to hypothesize a world where other resources circulate too; where regeneration beyond biological reproduction might be considered a valuable form of meaning-making; and where incursion is its own reward.

Anal utopia

According to Paul Preciado in an essay called ‘Anal Terror’, patriarchal capitalism could only emerge through a centuries-long process of ‘anal castration’: the denial (sealing-up) of any orifice that cannot be reduced to sexual or reproductive functions – especially the orifice through which bodily compost exits our bodies enters the earth. That is, the anus. In another historical process of corporeal enclosure, ‘It was necessary to close up the anus to sublimate pansexual desire, transforming it into the social bond, just as it was necessary to enclose the commons to mark out private property,’ writes Preciado. ‘To close up the anus so that the sexual energy that could flow through it would become honorable and healthy male camaraderie, linguistic exchange, communication, media, advertising, and capital.’ Borrowing Hyde’s terms, to close the anus is to restrict the movement of the gift, which accrues rather than loses value as it exits the body and becomes independent of the self.

With the concept of anal castration, Preciado asks where desire and life emerge. The anus is threatening precisely because it is sexy and productive – even reproductive, if shit is understood as manure from which new life grows. Yet that new life is not, at least in the first stage, human life. The worldview required to un-castrate the anus, to reach toward an ‘anal utopia,’ as Preciado has it, would require one to consider nonhuman species as part of an ecosystem in which shit is essential food rather than toxic waste. ‘The community of closed anuses is shored up with dumb columns made of families, with their anally-castrated-father and their hollow-viscera-mother . . . The kids with castrated anuses built a community they called City, State, Nation.’ This community is limited not only to those whose anuses are closed but to those who see the telos of all life as capital production and biological reproduction.

Where would all that erotic energy go to, in the anal utopia? If all orifices were understood to be potentially erotic – the nostrils, the pores of the skin – and all orifices were seen as (re)productive? If productivity was besides the point? If bodies did not have ‘outsides and insides, marking zones of privilege and abject zones’? If desire were not seen as ‘a reserve of truth’ but rather as ‘an artifact that is culturally constructed, modeled by social violence, incentives and rewards, but also by fear of exclusion’? If desire were no longer a marker of identity, by which one is made queer or femme or whatever else? If desire were instead seen as ‘an arbitrary slice of an uninterrupted and polyvocal flow’? If interpenetration were understood as a constant fact rather than a means to a reproductive end? Erotic energy could be made political by being made ecological.

Sophie Lewis, author of Full Surrogacy Now, reaches toward anal utopia through the concept of surrogate gestation. She begins by calling the work of gestation what it is: labor, and then asks how that labor could be distributed beyond the family unit, abolishing the family unit and its teleology in the process. In an interview, Lewis says: ‘If everything is surrogacy, the whole question of original or “natural” relationships falls by the wayside. In that sense, what surrogacy means is standing in for one another, caring for one another, making one another. It’s a word to describe the very actual but also utopian fact that we are the makers of one another, and we can learn to act like it.’ We are the makers of one another, and also the makers and the products of trillions of other species – we gestate and are gestated by them. We co-create the atmosphere, and we can learn to act like it.

Back to plants!

Interpenetration is necessary for all life. This, writes Emanuele Coccia, is a lesson taught best by botany. In The Life of Plants, Coccia argues that plants are ‘the paradigm of immersion’ in that they are contiguous with their environments. ‘One cannot separate the plant – neither physically nor metaphysically – from the world that accommodates it.’ The plant draws nutrients from its immediate access to earth, air and sun, and in doing so, it produces the conditions, the literal environmental necessities of nutrients and minerals, for all life, which rots and regrows. ‘All the forms capable of photosynthesis [are] domestic titans that do not need violence to found new worlds.’ By ‘new worlds’ Coccia means new ecosystems, but also new cosmologies, ways of explaining where life comes from and what it is for.

‘Plants, then, allow us to understand that immersion is not a simple spatial determination: to be immersed is not reducible to finding oneself in something that surrounds and penetrates us.’ Immersion is not one-way but rather a type of ‘mutual compenetration’, continuous and constant. That is to say that ‘for there to be immersion, subject and environment have to actively penetrate each other; otherwise one would speak simply of juxtaposition or contiguity between two bodies touching at their extremities.’ A world is forged through compenetration or immersion; immersion is always reciprocal. To seal up the anus is not only sad but futile; it pretends penetration is one-way and directional. Compenetration is intoxicating. Trying to prevent it is toxic.

On the back cover of the 2019 English edition of Coccia’s book, Bruno Latour gives a somewhat back-handed endorsement. ‘Back to animals! Back to mushrooms! And now back to plants!’ Latour refers to the recent spate of popular writing on the nonhuman world, the sometimes-romantic ‘post-Anthropocene’ turn to nature in the arts and humanities. The reasons are obvious: humans have fucked up the planet, exalting our own presence, progress, and needs for centuries, and now we have no choice but to attend to what we’ve overlooked and destroyed.

For a while, ‘back to the land’ was the goal. Kombucha on tap. Probiotics. Fecal transplants. Paleo diets. Craft breweries. Don’t clean your children; dirt is natural; replenish your gut; humans weren’t ‘meant’ to eat processed foods. Now, in 2020, Covid-19 has prompted a rapid reversal: fastidious hygiene, disinfection, quarantine, separation. Nature is benevolent, or nature is the enemy. Either way, the achievement of health is premised on the ability to control what enters and exits the body’s borders. Although the variables may change, the border remains. This is far from progress toward the ‘anal utopia’ Preciado asks for: it is simply the ongoing redefinition of purity according to new terms.

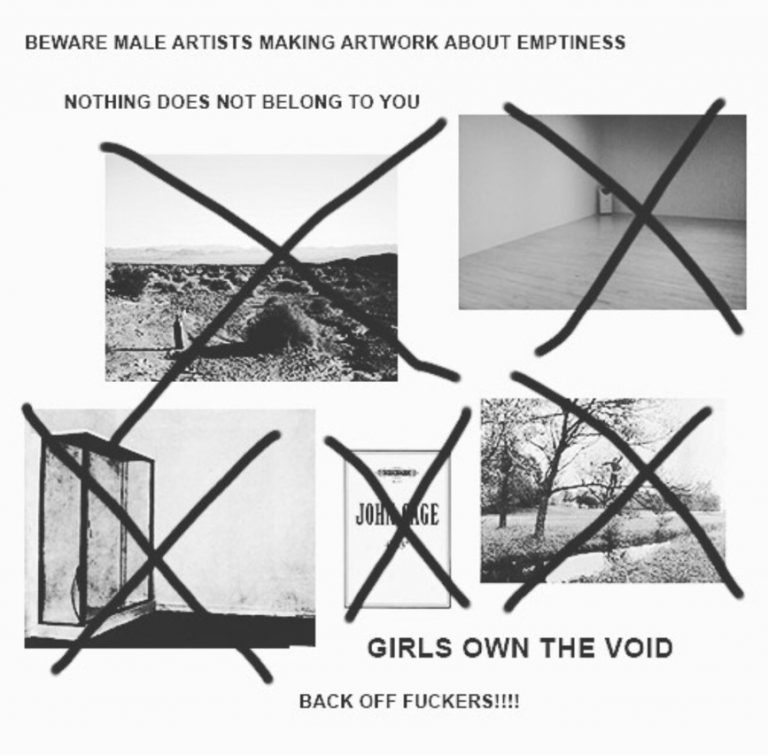

There can be no direct reversal of the Anthropocene and its processes of enclosure. Symbiosis cannot be recreated where it has been lost. Lost elements of ecosystems have already changed those ecosystems with their absence to the extent that reinstating them will not have the desired effects. There are toxic materials in the soil and the air – corporations and governments have put them there – and this is now nature; there is nothing to go ‘back’ to. Anyway, ‘back to nature’ would require more women’s work. Essentialisms about feminine porosity and the resulting kinship with the natural world are well known. The feminized body, like feminized nature, was enclosed precisely so that it could be penetrated, so it could do the work of penetration. In response, women and femmes have become expert at boundary dissolution. ‘Girls own the void’, as Audrey Wollen’s beloved meme proclaims, because girls learned over centuries how to power-bottom, how to reclaim the ‘hollow viscera’. But everyone’s got holes. Breathing is reproductive; it births the atmosphere. Shit is reproductive; it births the atmosphere. Dying is reproductive; it births the atmosphere.

No amount of disintegration or porousness makes us any less human. One can remain human while being mixed up – because to be human is to be mixed up. Coccia writes that ‘If things form a world, it is because they mix without losing their identity.’ Recalling Carson, the same could be said of love. Although it is described in terms of choice and desire, compenetration is a fact. To encounter Eros on the species level will entail all the risk and joy, death and regeneration, intoxication and toxicity, that human erotic love entails. Writes Hyde: ‘As vegetable life has the chemistry of compost . . . we humans may clean our animal blood through the chemistry of love.’

In a text ostensibly offering advice to young writers, Ottessa Moshfegh likens the process of writing to the process of self-fertilization – producing and feeding off of her own compost. She says that ‘in writing, I think a lot about how to shit. What kind of stink do I want to make in the world? My new shit becomes the shit I eat. I learn by digesting my own delusions. It’s often very disgusting.’ Forget species perpetuation – in this model, writing is reproductive, and its product is the creative gift. In this model, reproductive labor requires bodily boundary transgression through the collaborative work of the species of the digestive tract. In this model writing, like fucking, requires no femme fertility, only fertilizer. Working and loving this way may be very disgusting. It may also be very intoxicating.

With thanks to McKenzie Wark, Eugene Thacker, Andreas Petrossiants and Tiffany Sia.

Image © Ken-ichi Ueda